Running is always a part of every person’s life. Running seems to get harder and harder. Sometimes, it feels like the spring has worn out, the engine is stalling or the joints need a good lubrication. Or is it just psychological? Or is it physical limitation? It comes to a point to look for some answers. Reactive strength popped up.

What is reactive strength?

Reactive strength is a representation of the fast stretch shortening cycle (SSC) function to increase subsequent force production.

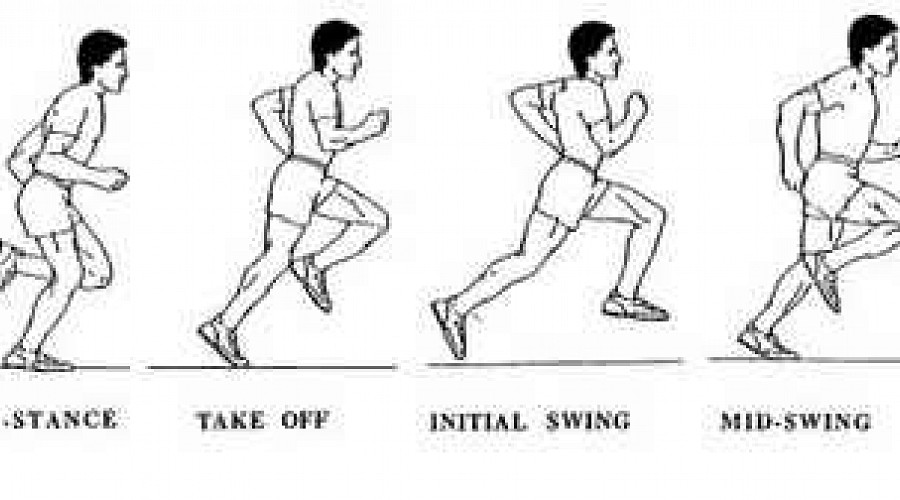

It shows athletes’ ability to change quickly from an eccentric to a concentric contraction and their ability to develop maximal forces in minimal time. It has also been described as a measurement of stress on the calf/Achilles muscle/tendon system.

The faster athletes have significantly shorter ground contact times from stride to stride in 10m sprints in comparison with the slower counterparts. Players faster in the change of direction test demonstrated much higher reactive strength abilities (>25% difference) than their slower counterparts. The push-off involved in rapid change of direction tasks involves a fast SSC muscle action of the hip, knee, and ankle leg extensors

The quality of reactive strength translates into allowing faster athletes to tolerated a higher eccentric loads, and convert this into concentric force over a shorter period of time which is essential in sports performance.

How do you assess reactive strength?

It is assessed primarily through the RSI. It is a simple ratio involving two metrics:

- How high can you jump?

- How fast can you jump?

The index is calculated by dividing the height jumped with the ground contact time. For example, an athlete jumping 50cm (0.5m) with a contact time of 200ms (0.2s) would score an RSI of 2.5 units.

The RSI can be improved by increasing jump height or decreasing ground contact time.

How does this affect endurance running?

Elite distance runners demonstrate ground contact measures that suggest that known differences in running economy between sexes and event specialties may be a result of differences in running gait. Any change in ground contact time may have relationship with race performance. It is suggested that the ground contact time is shorter at first 400m and increase over the distance gradually. Sometimes adjusting the foot–ground contact biomechanics of a runner with the aim of maximising running economy, a trade-off between a midfoot strike and a long contact time must be pursued. Midfoot strikers showed a significantly shorter mean contact time and lesser oxygen intake as compared to rearfoot strikers.

In runners, improvements were found in running economy with 9 weeks reactive strength training intervention.

How does it work?

It takes about 4 to 6 weeks of high intensity power training without fatiguing the central nervous system. It is believed that the neuromuscular adaptations contributing to explosive power may occur early (within the first two weeks).

By using the myotatic stretch reflex to the muscle to produce an explosive reaction, plyometrics is believed to be the link between speed and strength. Strength training involving the key muscles group such as the glutes, quadriceps and hamstrings are important.

The focus is to optimising the power flow of linear and rotational energy transfer that occurs during the transition from eccentric to concentric muscle contraction.

How to do it?

Plyometric program progressed from low to moderate-high intensity drills, thus gradually imposing a greater eccentric stress on the musculotendon unit.

Training volume was defined by the number of foot contacts made during each session, starting with 72 contacts in the first session, increasing to 106 contacts in the final 2 sessions. Plyometric drills lasted approximately 5–10 seconds, and at least 90 seconds rest was allowed after each set

Plyometric drills included standing vertical and horizontal jumps, lateral jumps, ankle hops, skipping, single leg hopping, maximal hopping, and low-level drop jumps (20 cm).

It is important to maintain the form when the fatigue starts to set in.

References:

- Beattie, K., Kenny, I. C., Lyons, M., & Carson, B. P. (2014). The effect of strength training on performance in endurance athletes. Sports Medicine, 44(6), 845-865.

- Beattie, K., Carson, B. P., Lyons, M., Rossiter, A., & Kenny, I. C. (2017). The effect of strength training on performance indicators in distance runners. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 31(1), 9-23.

- Beattie, K., Carson, B. P., Lyons, M., & Kenny, I. C. (2017). The relationship between maximal strength and reactive strength. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 12(4), 548-553.

- Chapman, R. F., Laymon, A. S., Wilhite, D. P., Mckenzie, J. M., Tanner, D. A., & Stager, J. M. (2012). Ground contact time as an indicator of metabolic cost in elite distance runners. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 44(5), 917-925.

- Flanagan, E. P., & Comyns, T. M. (2008). The Use of Contact Time and the Reactive Strength Index to Optimize Fast Stretch-Shortening Cycle Training. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 30(5), 32-38. doi:10.1519/ssc.0b013e318187e25b

- Flanagan, E. P., Ebben, W. P., & Jensen, R. L. (2008). Reliability of the Reactive Strength Index and Time to Stabilization During Depth Jumps. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 22(5), 1677-1682. doi:10.1519/jsc.0b013e318182034b

- Lloyd, R. S., Oliver, J. L., Hughes, M. G., & Williams, C. A. (2012). The Effects of 4-Weeks of Plyometric Training on Reactive Strength Index and Leg Stiffness in Male Youths. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 26(10), 2812-2819. doi:10.1519/jsc.0b013e318242d2ec

- Markovic, G., & Mikulic, P. (2010). Neuro-musculoskeletal and performance adaptations to lower-extremity plyometric training. Sports medicine, 40(10), 859-895.

- McClymont, D. (2005, May). Use of the reactive strength index (RSI) as an indicator of plyometric training conditions. In Science in Football V: The Proceedings of the Fifth World Congress on Science and Football. London, Routledge (pp. 423-432).

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQsHRWokajM

Countermovement jump

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aCgyNYtd--E

Contributed by Trevor Lee